Watershed Urbanism

Healthy watersheds deliver 17 critical ecosystem services whose value can no longer remain outside systems of exchange within the city. The important components of a riparian system, whether it is a first order headwater stream or an 11th order stream like the Mississippi River, include a floodplain, riparian banks, and the stream channel. Riparian system health is directly tied to this normative geomorphological structure governing its water and sediment flows, biogeochemical properties, and nutrient exchange―or stream metabolism.

Historically, planners never knew what to do with water. When urban streams and their wetlands are not drained, diverted, or piped, they are channelized as conveyance for waste removal and freight transport, resulting in chronic environmental impairment or “urban stream syndrome”. The consequences of this development-centric legacy still linger as 50% of the nation’s rivers and streams, 66% of its lakes, reservoirs, and ponds, 64% of its bays and estuaries, and 82% of its ocean and near coastal waters are classified as environmentally impaired by the EPA, meaning they do not meet water quality standards supportive of drinking, swimming, or fishing.

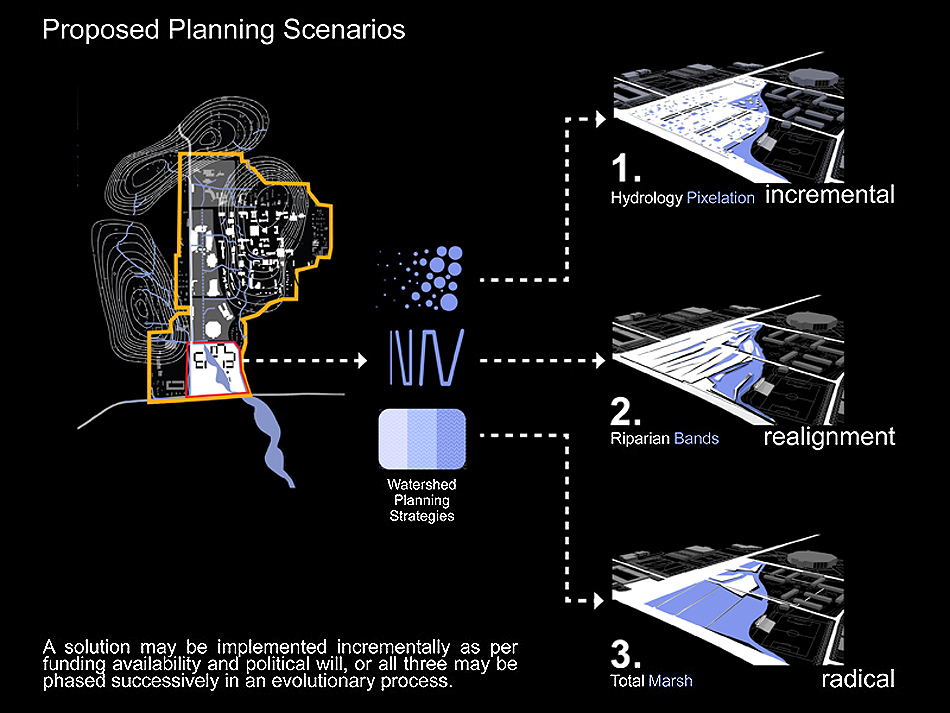

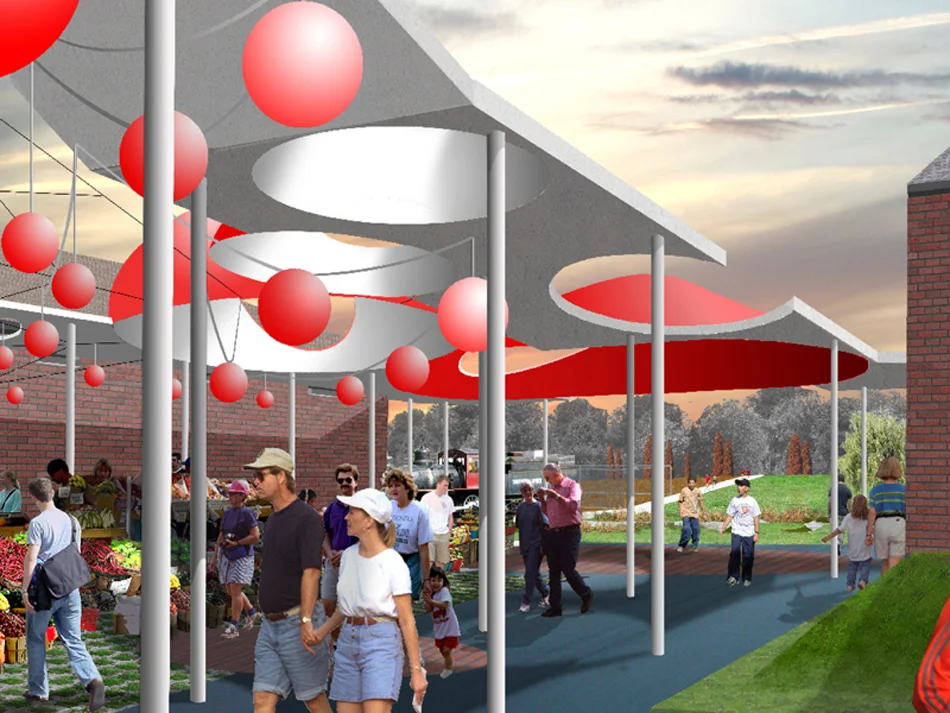

Watershed Urbanism proposes a “rewilding” of riparian corridors to restore lost ecological functioning while forming well-amenitized urban networks of linear parks, neighborhood open spaces, and pedestrian facilities.